This is the question I kept asking myself: Why would anyone want to kill Dr. Fauci?

Stopping at a Kroger outside of Roanoke, Virginia, for gas and supplies on the way back from loading my Dad’s belongings onto a trailer for his move back to North Carolina after 40 years, I was the only person I saw wearing a mask. Not even the employees.

A teenaged girl who looked to weigh about ninety pounds lost control of the stack of six buggies she was pushing from the parking lot and I grabbed one that got away and pushed it up to the stack with the others. She looked at me oddly wearing my mask Mom had made me and the black gloves she’d given me for my birthday at the onset of the plague, and said, Thank you sir.

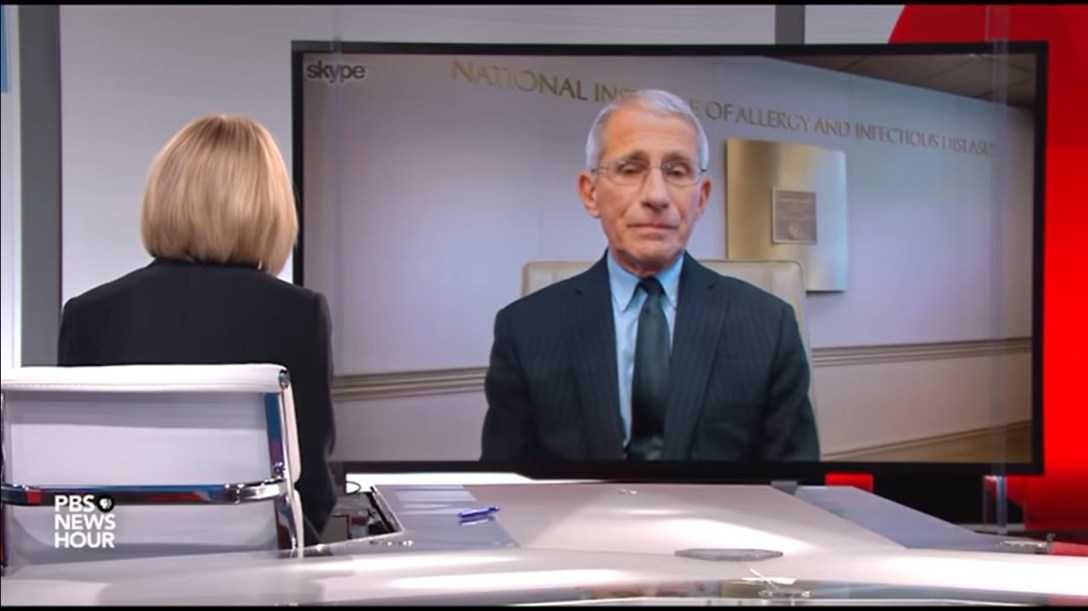

People in the Kroger stared at me with curious smiles, going about their business as if it were just another beautiful spring day in the mountains. Have they not heard what Dr. Fauci told us? Just last night I watched him on the PBS News Hour stressing the importance of wearing masks, to keep others safe in case you were infected and didn’t know it because you weren’t coughing or running a fever or your throat wasn’t hurting or you didn’t feel like you were trying to breathe under water. Did they not hear Dr. Fauci say you could catch the virus from someone talking at you?

If it had been a year ago — no, a month ago, which seemed like a year ago (BC, before Coronavirus, or AD, After Disease, with the hope that the interim wasn’t also 33 years) — then the scene inside the Kroger would not have been surreal. People laughing and checking out and saying, Hi ya, Joe! and standing beside one another with carefree abandon and no whiff of what the hell “social distancing” was.

I walked into the bathroom to wash my hands and saw a man in his early twenties wearing a maroon sweatshirt with mustard lettering that said Virginia Tech, long hair tied in a ponytail and a scruffy goatee, and wearing a mask. I washed my hands and looked around for the towels — VA Tech was standing in front of the only dispenser. We looked at each other, each with knowing caution in our eyes, as if we were fellow soldiers and the only people in this particular world who understood that the enemy was among us. Hey man, here ya go, he said, pivoting respectfully out of the way.

As I walked down the aisles, people politely gave me extra berth — a man in his thirties with close-cropped light brown hair and a polo shirt and crisp khaki shorts who looked like he’d just come from coaching a basketball team smiled at me and said, Hello, as he moved out of the way of the oatmeal.

A pretty cashier in her fifties named Binnie asked for my ID for the beer. She looked at my picture and smiled and said, Oh, you’re very handsome without that mask on! I smiled and said, So are you!, and we both laughed. Pushing my cart out of the store, I saw the young girl with the buggies giggling with another young girl co-worker, pushing her on her back.

While I walked around the trailer hitched to my brother’s truck to make sure everything was tight before pulling out for the rest of my journey, I heard someone coughing violently. I turned around to see a rough looking man in his fifties with silver hair and a handlebar moustache hanging out of the shotgun window of a muddy black pickup truck, his torso flopping, sun-tanned muscular arms waving from a gray T-shirt.

Help! Help me! Somebody call 911, I done got the Co-Vid! His buddy was in the driver’s seat looking at me and dying laughing.

They said last night on the News Hour that Dr. Fauci is getting threats against his life — Judy Woodruff asked him how that made him feel, if his job was now something more than he bargained for. “You know Judy, this is the life I’ve chosen, and I accept it.”

Dr. Fauci was a well-known activist during the AIDS crisis. He nobly challenged racism and homophobia when racism and homophobia were still as American as apple pie (before America was Made Great Again and racism and homophobia became as American as apple pie again.)

Anthony Fauci (precariously) holds the same post he had under Ronald Reagan four decades and six administrations ago — the country’s top doc and trusted leader for infectious diseases.

At a time when men were proudly arrested for loving one another in America, Dr. Fauci “loosened clinical trial requirements for HIV-drugs so that a far greater number of desperate patients could try new compounds (an approach called “parallel tracking”), expanded research on HIV/AIDS and its treatment in underrepresented women and people of color, and gave activists and people living with HIV seats at the table of the planning committee of the AIDS Clinical Trials Group.” Despite this controversial courage, he survived conservative Presidents Reagan and both Bushes, only to run into the evangelical mouthpiece whose rise to tv-show fame — and primary weapon for protecting his office — is the phrase, “You’re fired.”

At the end of his interview, the seventy-nine-year-old Dr. Fauci confided to Judy Woodruff that he did have one regret about the death threats. “The thing I don’t like is the effect it has on my family.”

I wondered if the men laughing at my mask and my fear had ever heard of Albany (all-BINNY if you’re from down there), Georgia, a big, small town on the way to Florida, with sandy roads and no interstate and plenty of churches, 30 minutes from Plains, Georgia, where Jimmy Carter still teaches Sunday School. Albany is home to 75,000 people — about the size of Roanoke. 75,000, as we say, good people, the kind of people I know well, having once married into a family from Cordele, right around the corner.

Albany now has a new distinction — death. Albany, Georgia, has the fourth highest rate per-capita of COVID-19 cases in America. 1,100 Albanians have been infected by the coronavirus, 72 have died.

You have to be from a small town to understand what that means. “Everybody knows everybody.” In a place like Albany, Georgia, with that many infections and that many dead, everybody knows somebody who knows somebody who got sick, or who died.

Albany, Georgia, is a place where funerals overflow with mourners and food, sweet tea and casseroles and fried chicken and pies, like the funeral for retired janitor Andrew Mitchell on February 29. People cried, and wiped their faces, and hugged and kissed their loved ones and friends and shared their tears and spread the coronavirus, at this funeral and another one, until there would be 72 more funerals in Albany in less than a month.

Six of Andy Mitchell’s brothers and sisters contracted the coronavirus. The only hospital in Albany, Phoebe Putney, ran out of their six-month stockpile of protective equipment in seven days, and was so overrun with sick patients that nurses were told to keep working even if they tested positive for the virus.

Pastor Simmons of Mt. Zion Baptist Church in Albany read text messages he’d received to the New York Times. “Please continue to pray,” one said. “My mother, my grandmother and my grandfather have been admitted to the ER with coronavirus symptoms.”

Then, later, “My mother has died.”

Still grieving from the loss of her brother, Andy Mitchell’s sister Dorothy Johnson, an oncology nurse, soon had to plan another funeral, for her daughter Tanya. Her best friend. Dorothy unplugged Tanya’s ventilators and removed the IV tubes from her body.

What if the buddy of the guy who was hanging out the window of the pickup truck in Roanoke, Virginia, had died, the guy who was beside him laughing, a friend he probably grew up with and knew all his life, like the friends of Dorothy’s daughter Tonya in Albany, Georgia, knew her.

I couldn’t understand. Why were there death threats against Dr. Fauci? Who would want to kill Dr. Fauci? He is helping us. He is saving lives. He is giving us information to help us.

He is giving us information the men in the pickup truck don’t want because they have rent to pay and truck payments and families to feed and it’s taking away their jobs.

How many more rural funerals will it take.

I wasn’t angry when I lifted my phone, just sad. “Hey look, he’s takin pitchers.”

Driving out of the Kroger parking lot towards the highway to North Carolina, I checked my mirror for the black pickup truck.